Essays

Daniel Ridgway Knight

(1839-1924)

Early Years

The American painter Daniel Ridgway Knight spent most of his career in France, but his early life was in Philadelphia, which was a cultural center for the visual arts throughout the nineteenth century. Knight was born on March 15, 1839, to Robert Tower Knight and Anna Shryock, and baptized on August 18, 1839, at St. George Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.[1] He was the third child, and the first son, in the family; two other siblings would follow in the ensuing years. Anna and Robert Knight are recorded in the US Census as living in Philadelphia in 1830 and 1840, but by 1850, the family had moved to the small town of Guilford, Pennsylvania, four miles east of Chambersburg.[2] Ten years later, they are listed in the 1860 census for Philadelphia again.[3] Robert Knight was listed as a “carpenter/builder” in 1860 and in 1870 as a “civil engineer”.[4]

Little is known about Knight’s early schooling or how he developed an interest in the visual arts. Perhaps his father’s work as a builder and engineer introduced him to the study of design. By 1858 he was enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) where he received foundational instruction in art and began to study painting.[5] Knight would undoubtedly have been exposed to a variety of artistic trends at PAFA including the French academic teaching methods that were the standard in European art schools, including PAFA’s first “blockbuster” exhibition in 1858. Entitled Modern British Art in America, the show toured New York, Philadelphia and Boston, all cultural centers with thriving arts communities at the time. The exhibition featured the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, displaying 105 oil paintings and 127 watercolors at the Philadelphia venue. Local critical reactions were mixed. The Pennsylvania Inquirer claimed that “the surprising excellence of many of the specimens so far exceeded our anticipation that they excited surprise as well as intense admiration” while the Sunday Dispatch had few positive remarks to offer, noting that the Pre-Raphaelite paintings were “rigid, false and too Catholic”.[6] For the students at PAFA, the show provided a glimpse of what was then experimental European art unlike anything they had seen before. The most popular of the artists represented was Ford Madox Brown, whose paintings of King Lear and The Light of the World were singularly well received; in addition, there were works by John Ruskin, Elizabeth Siddal, William Holman Hunt, and J. R. Spencer Stanhope. The influence of these painters on Knight’s later work is particularly evident in his attention to richly textured landscapes.

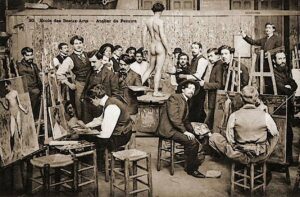

The next few years in Knight’s career were full of new experiences. He is registered in the 1860 US federal census as still living in his parent’s home in Philadelphia in the spring, but it is likely that he left for Paris shortly thereafter.[7] He applied to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts promptly, but began his study in the atelier of the Swiss painter, Charles Gleyre (1806-1874), who had taken over Paul Delaroche’s studio in 1843. Gleyre had no teaching experience when he agreed to take on Delaroche’s students, but he turned out to be an insightful and progressive studio master.[8] When Knight arrived, there were at least two other young Americans studying with Gleyre, Edward Larson Henry (1841-1919) and William Mark Fisher (1841-1923). Henry had also studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1850s, so he and Knight would certainly have been acquaintances, if not friends. By 1862, there were several other noteworthy students working at Gleyre’s atelier, which had by then developed a reputation for being an innovative and open-minded environment. Those students included Pierre Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, Alfred Sisley and occasionally Claude Monet. There are no records indicating how much Knight and his American colleagues interacted with the young Impressionist painters, but surely, there must have been lively conversations in the studio. During this time, Knight was also studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where he matriculated in 1861.[9] (fig. 1) Following his time in Paris, Knight headed for Rome, where he could study the masterworks from both the classical period and the Renaissance.[10]

In 1863, both Knight and Edward Larson Henry returned to the United States, possibly because of the passage of the Enrollment Act, which required that all male citizens between the ages of 20 and 45 were subject to conscription. With intense fighting in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in July of 1863, there was a dire need for additional troops. The existing military records for Philadelphia do not indicate that Knight was ever called to serve, although the Civil War records are often incomplete. What is known about Knight’s work during the Civil War era is a painting of a diverse group of people sheltering inside a barn while a terrible fire burns outside. Although the title of the painting had long been assumed to be The Burning of Chambersburg, art historian Elizabeth Johns has established that Knight himself entitled it Union Refugees. (fig. 2) It is atypical in Knight’s career, but the reference to Chambersburg may provide a clue about why the painter chose this subject. His mother Anna Shyrock, was born there, and Knight himself had lived in Guilford near Chambersburg in the 1850s. As Johns suggested, it may have been created as “a “memorial to the people of the town.”[11]

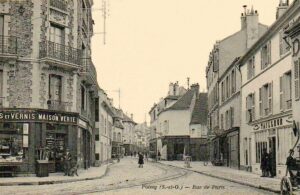

Back in Philadelphia, Knight established a portrait studio where he also accepted pupils. One of them was a young woman named Rebecca Morris Webster (1849-1911), whom Knight would marry on September 20, 1871, in St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.[12] Just a few months later, the newlyweds moved to France, settling first in Paris and ultimately in the town of Poissy fifteen miles northwest of the city. (fig. 3) Their arrival in Paris could not have come at a less propitious moment. The city was still reeling from the destruction caused by the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. (fig. 4) Although the fighting was over by the time the newlyweds arrived, the political tensions remained intense. France was still

occupied by the Prussian army and faced a crushing war debt. With the national infrastructure in ruins and its economy shattered, the leaders of the new Third Republic were challenged to come up with a strategy that would allow them to pay off the war debt—and send the Prussian soldiers packing. The central question was whether France had anything to offer the rest of Europe that would stabilize the economy while they were in the process of rebuilding the infrastructure. The answer they proposed was that France had a reputation for producing luxury goods on a global scale; fine food, fine wines, high fashion and jewelry, fine perfumes and above all, fine art. All of these products could be produced without industrialization and were likely to appeal to a wide market. As art historian Paul Tucker wrote in The New Painting, “Art, in fact, was the one thing that the country, despite its ruinous condition could point to as unscathed and incontestably superior to that of other European countries. The government recognized this and took appropriate measures.”[13] Clearly this was a gamble, but it was paired with a public campaign to buy very inexpensive bonds. In other words, ordinary people could buy into the nation’s recovery effort at very affordable prices. For artists, it would eventually enable a boom market, particularly as wealthy Americans became interested in creating private collections.[14]

At Home in Poissy

fig. 5. The Poissy enclosure of the abbey, ca. 1875-1880. From left to right, Meissonier’s house, Ridgway Knight’s house) and Notre-Dame collegiate church. Photographer Agnès Guignard

Knight’s primary reason for moving to Poissy was the presence of Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), a painter he much admired from his first visit to France. Meissonier had purchased a dilapidated mansion there in 1846 at the height of his artistic success, and subsequently created both a winter studio at the top of his house and a summer studio in a glass-roofed annex. (figs 5 and 6) The site was adjacent to the ancient boundaries of a royal priory that was founded in 1304 by Philippe le Bel, the grandson of king Louis IX who was canonized in 1297.[15] With the exception of the original gatehouse, everything inside the priory enclosure was destroyed during the French Revolution. Meissonier’s house was originally an orangerie located just outside the walls. There, he would work with a selected number of students, including his own son Charles (1844-1917), and after 1872, Daniel Ridgway Knight. According to Poissy historian Agnès Guignard, Meissonier accepted only seven students on a regular basis, two of whom were related to him either by birth or marriage.[16] The daily routine would typically consist of morning sessions in one of the studios at Meissonier’s house followed by plein air painting in the afternoons among the forest and river landscapes native to Poissy. Given Meissonier’s meticulous attention to detail in his own work, it comes as no surprise to learn that he emphasized the study of nature and attention to realistic imagery in his teaching. He generally followed the curriculum of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris with its focus on creating many sketches before beginning to paint. In addition, he often used clay or wax models to evaluate the way that light would hit a figure from different angles. Likewise, Meissonier did not shy away from the use of photography as an aide-memoire. When he purchased an adjacent farm building as a home for his son Charles in 1862, the space was renovated to include a glass studio appropriate for photographic work.[17] Each of Meissonier’s students also had a private studio on the grounds, thus creating a small, informal artists’ colony around the historic site, which eventually became known as the Abbaye.

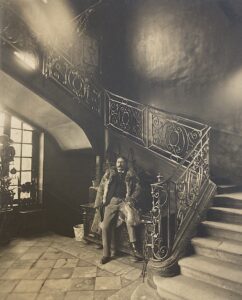

fig. 7. Daniel Ridgway Knight in the front hall of his home in Poissy. Album Daniel Ridgway Knight, 1883, un maison de campagne à Poissy (Poissy, France : 1883). Courtesy of the Insitut nationale d’histoire de l’art, Paris.

Knight’s early years in France are largely undocumented except for the birth of his first child, Louis Aston on August 3, 1873. By that time, he had purchased a large seventeenth-century house that bordered the enclosure of the medieval priory.[18] (fig. 7) Ernest and Charles Meissonier were now neighbors, and Knight was an active member of the small group of students working there. The 1876 census, however, lists only Knight himself, not his family at this address.[19] Whether Rebecca and Louis were still living in Paris, or perhaps with the Meissonnier family nearby is unknown. It is likely that Knight’s house required considerable renovation before it was suitable for family life. Charles Meissonier and the painter Lucien Gros (1845-1913) also had homes nearby along with their families and servants. The painter Sidney Arboine purchased a house just beyond the boundaries of L’Abbaye and Maurice Courant almost certainly had a studio on the premises although its exact location has not yet been identified.[20] Knight’s home next to Ernest Meissonier’s allowed his family to be part of the artist’s community as well. In addition, he has a separate studio nearby.

Knight’s painting during these years benefitted from the artistic ferment of the post-war era. His former studio-mates from Gleyre’s atelier were creating a stir with their Impressionist exhibitions of avant-garde art in venues that were independent of the official Salon. The Barbizon generation that revolutionized landscape painting in the 1830s were at last being honored as visionary artists; and the Realist painters and sculptors of the 1850s and 1860s were providing inspiration and guidance to the younger generation. Equally important, a group of naturalist painters such as Jules Bastien-Lepage and Julien Dupré were beginning to attract attention. Knight’s work was closest to that of the Naturalist painters, all of whom owed a debt to the earlier work of Jean-François Millet, whose death in 1875 prompted a substantive re-evaluation of his work. Some of Knight’s most ambitious compositions date from this period. His earlier work consisted largely of anecdotal and literary scenes, many of which he sent to the annual exhibitions at the National Academy of Design in New York. Les Fugitifs is one example. (fig. 8) Dating from 1873, it suggests a literary source, probably from a gothic novel or one of Sir Walter Scott’s medieval tales, perhaps Ivanhoe. It is full of melodrama as the young couple and their older companion attempt to escape by boat while a friendly peasant keeps watch on the castle in the distance. Literary genre painting was very popular and Knight may also have been accustomed to painting these types of images when he was still in Philadelphia. It was exhibited at the Salon of 1873 in Paris.

Like Dupré and Bastien-Lepage, Knight was intrigued with rural scenes of working people. His submission to the Salon in 1875 reflected this interest in a scene of washerwomen hard at work along the Seine, Les Laveuses. (fig. 9). The serenity of the women chatting together as they launder their clothing echoes the scenes of an earlier American painter, George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), but the sophisticated composition and attention to detail reflects the central influence of Ernest Meissonier on his student’s work. It was no doubt because of Knight’s affiliation with the older master that this painting received considerable attention at the Salon of 1875. The subject matter, too, implied that Knight was one of the emerging Naturalist painters in France, preferring to portray the rural working class rather than urban life. It must be noted though that the actual women who worked as laundresses did not wear such pristine clothing. As William Gerdts remarked about the painting, Life is Sweet (Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio): “His academic training tells in his images of attractive young female peasants such as Life is Sweet. They are usually posed among bushes of flowers whose loveliness equals that of the figure, a popular subject on both sides of the Atlantic which emphatically denies the rigors of peasant life.”[21] Knight’s career began to develop rapidly after his success at the Salon.

The 1870s also brought sad news. Knight’s father Robert died in 1873 followed by his mother Anna in 1879. In between their deaths, however, a second child, Charles Meissonnier, was born on November 27, 1877, in Poissy. As France recovered from the Franco-Prussian War, more and more American artists began to arrive.[22] Many were attracted to Paris of course, but there were also sizeable American artists’ colonies in Brittany and in Giverny near Monet’s home in Normandy. Knight seems to have spent time painting in Brittany, although he was never associated with any of the numerous artists’ colonies there. His preferred subject matter was increasingly depictions of peasant women engaged in rural labor or simply relaxing with each other. The fields and rivers of Brittany and Normandy provided ample inspiration for such scenes.

fig. 10. Jean Béraud, Après l’office à l’église de la Sainte Trinité, actuelle Cathédrale américaine de Paris, Noël 1890, Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

The Knight family also maintained close ties to Paris. The railway between Poissy and the capital opened in May 1843; it was rebuilt again in the early 1870s after the Franco-Prussian War. With convenient access to Paris, Knight could travel to meet with his art dealers such as Knoedler and Boussod & Vallodon. He also seems to have maintained a studio in the city at varying times throughout his career. On Sunday morning, the family would have been in attendance at the American Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, one of the uniquely American gathering places in the city.[23] Known colloquially as the “American Cathedral of Paris”, this Episcopalian church is located on the Avenue George V, just off the Champs-Elysées in one of the wealthiest quarters of the city. It was founded by expatriate Americans in the 1830s and gradually grew in size and scope until it became a significant cultural center for English-speaking residents of Paris. In fact, the French artist Jean Béraud found the sight of American artists exiting the church on a Sunday morning to be a spectacle worth painting. His canvas, After the Service at Holy Trinity Church, Christmas, 1890, depicts the fashionable crowd as they exit the Gothic Revival church into a wintry Paris day. (fig. 10) The French and US flags hanging above the main entrance provide a colorful counterpoint to the gloomy grey skies above. Today, the original painting hangs in the Carnavalet Museum, but there is also a réplique at the cathedral. Well-known members of the congregation included John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler when he was in town, but more importantly, it was a place where all American artists could congregate for social activities and conversation. Daniel Ridgway Knight was actively involved in helping to plan and design many of the exhibitions that were held at the church.[24]

fig. 11. Daniel Ridgway Knight painting in the garden of his home. Album Daniel Ridgway Knight, 1883, un maison de campagne à Poissy (Poissy, France : 1883).

Courtesy of the Insitut nationale d’histoire de l’art, Paris.

The decade of the 1880s brought continued success. Knight’s paintings were selling well and he had established a reputation in mainstream art circles. A third son, Raymond Ridgway, was born in 1883, completing the family and bringing the number of people living in the Poissy house to nine. In addition to working in the house, the servants occasionally posed for Knight’s paintings. The house itself was very imposing; three stories high with large reception rooms full of ornate Louis XIII-style furnishings, and eventually a considerable art collection as well. Knight’s paintings of course are most prominent, but there is also a group of large seventeenth-century tapestries woven in Bruges. The extensive garden provided a picturesque respite from daily activities as well as a charming background where Knight—and eventually his son Louis—could stage vignettes for painting. (fig. 11)

Knight’s career flourished during this period. His painting entitled Hailing the Ferry not only won a third class medal at the Salon of 1888, but also a silver medal at the annual Munich exhibition that same year. (fig. 12) The following year, the city of Paris celebrated the centennial of the French revolution with an extravagant international exposition. The crowning attraction—and the most controversial—was the Eiffel Tower, a tribute to France’s industrial recovery after the Franco-Prussian War as well as a very public statement of the national commitment to a republican form of government based on the concepts of liberty, equality and brotherhood. In this heady atmosphere, Knight received a silver medal for painting at the Exposition universelle, and on November 27, 1889, was inducted into the French Legion of Honor. He would subsequently become an officer of the Legion on January 26, 1909.[25]

The 1890s opened with considerable optimism as France celebrated its prosperity and its revitalized leadership role in international affairs. American artists continued to stream into the country in ever-growing numbers. Some would stay for a few months, some for a few years, and some for most of their lives. Daniel Ridgway Knight certainly appeared to be one of the lifetime expatriates when the decade opened. He had settled into a comfortable existence in Poissy, having purchased a substantial property and enjoyed an artistic career that was rewarding both financially and personally. The 1891 census for Poissy lists the Knight family living on the rue des Dames; five years later in 1896, however, there is no record of them in any French census, either in Poissy or Paris. Nor is there any record of them living in the village of Rolleboise, where Knight would later purchase property.

Although this decade remains only partially documented, there are two facts that suggest a possible explanation for the abrupt disappearance of the entire Knight family from French census records. First is the decision by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to initiate a new Academy Gold Medal by honoring Daniel Ridgway Knight in February 1894.[26] The award was proposed by PAFA Board member John H. Convers to recognize “American painters and sculptors exhibiting in the academy, or represented in the collection, or for eminent services in the cause of art or to the Academy.”[27] Second is the death of Rebecca’s father Thomas Webster on December 30, 1894, in Philadelphia. Colonel Webster’s obituary in The Philadelphia Times notes that he had been ill for some time and had suffered a stroke in October 1894.[28] Together, these events suggest that the family may have returned to Philadelphia for the celebration of Knight’s work at PAFA and then stayed longer because of Thomas Webster’s ill health and death. If so, they were certainly in the US during all of 1894. Rebecca would naturally have wanted to stay with her mother and siblings in the immediate aftermath of her father’s death. Whether Knight himself returned to France sooner is unknown, although his absence from the 1896 census indicates that he was not living in Poissy. One possible explanation is that he was traveling through Normandy during these months as is indicated by the painting Shepherdess of Rolleboise that he submitted to the Salon in 1896.[29]

The extended stay in Philadelphia may also have been necessary so that Rebecca could participate in the legal processing of her father’s estate. This is supported by the 1901 Poissy census where Rebecca reappears as the “chef” (head of household). Her legal status is listed as rentier, which indicates that she was a “person of private means”. Her sons and husband are listed as members of the household, along with four servants. The additional financial security may have been an incentive for Knight to purchase property in the riverside village of Rolleboise, 25 miles northwest of Poissy (and five miles southeast of Monet’s home in Giverny).[30] The population of Rolleboise, then as now, has never topped 400 people.[31] According to a 1901 article in Brush and Pencil, Knight “secured a house with a fine garden, and built himself a studio” on a site midway between the river and the top of the surrounding bluffs.[32] The location is extraordinary; Rolleboise sits at the beginning of an oxbow curve in the Seine, giving it not only dramatic views northeast along the river bend, but also across a lush field bordering the river as it curves southwest to resume its course to the English Channel. Knight built a glass house studio there, and appears to have taken up permanent residence in Rolleboise along with his son Louis and two female servants. (fig. 13)

Back in Poissy, Rebecca remained at home on the avenue Meissonnier with her youngest son Raymond, then 23 years old. Charles Knight, aged 29 when the 1906 census was taken, had already moved to Paris where he had finished his architectural studies, married Alice Boucherie in 1903, and established his own design firm.[33] Meanwhile Louis married an American woman, Caroline Ridgway Brewster on October 15, 1907, in Somerset, New Jersey, and was living in New York much of the time.[34] When Rebecca Knight died in August 1909, she left her house to her son Charles and his growing family.[35] Two years later, on October 22, 1911, Raymond Knight died of an overdose of morphine while living in Paris.[36]

fig. 14. View of Bruges tapestries in the Sitting Room of Knight home, Poissy.Album Daniel Ridgway Knight, 1883, un maison de campagne à Poissy (Poissy, France :1883). Courtesy of the Insitut nationale d’histoire de l’art, Paris.

Following his wife’s death, Knight seems to have lived primarily at Rolleboise. Records indicate that he auctioned six large Bruges tapestries at the Hotel Drouot on March 10, 1910.[37] Originally hung on the walls of the grand salon in the house at Poissy, the tapestries were part of a series on Sciences and the Arts designed by the atelier of Peter Paul Rubens in 1674-1675. They are visible in a number of the photographs in the Album Daniel Ridgway Knight. (fig. 14) The sale provided Knight with 40,000ff in 1910, which is approximately $253,000 in 2025. Knight was able to continue his work at the studio in Rolleboise, occasionally accompanied by his son Louis, until the outbreak of World War I in 1913.

The War Intervenes

All foreigners living in France were asked to leave at the outset of the war. Other Europeans were required to leave, but Americans had a somewhat more negotiable position because the United States was neither at war with any nation nor a potential threat to France.[38] As the German Army advanced on the Ile-de-France, however, the house in Poissy was requisitioned by the military. Details about this turn of events are limited, but Knight and both of his sons applied for passports at the US embassy over the course of the next few years. By then they were all living in Paris according to the addresses listed on their applications.[39] These applications suggest strongly that all three men were traveling between the US and Paris during the war years, whether for business or family concerns. It must be noted that passports were not mandatory in the early twentieth century and were only haphazardly regulated at the outset of World War I.[40]

When he was in Paris, Knight was actively involved in helping the war effort through his activities within the arts community. In 1918, he donated one of his paintings to a benefit exhibition sponsored jointly by the Société des Artistes Français and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts; the event took place from May 1st to June 30th at the Petit Palais. Knight’s contribution was Les Terraces à Rolleboise, a scene of young women gathered on the hillside above the river Seine.[41] It is also likely that Knight was a member of an exhibition committee at the Church of the Holy Trinity, the American Cathedral of Paris, which sponsored a variety of benefit shows during the war.[42]

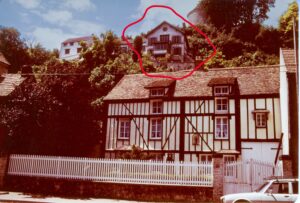

fig. 15. View of the house in Rolleboise from the summer of 1982. Robert Knight, photographer. Courtesy of Sara E. Knight

Particularly troubling during World War I was the disposition of the houses in both Rolleboise and Poissy. Charles Knight returned to Poissy in 1919 with his father who apparently lived there briefly as well.[43] Descendants of Charles Knight’s family recall stories about the house suffering considerable damage and possibly the loss of many of Knight’s artworks.[44] The house was sold in 1921 to Casimir Crosnier-Leconte, who was an auctioneer, and perhaps a family acquaintance.[45] Knight’s studio was destroyed shortly after the sale, and part of the house was razed in 1922. The reason for this demolition remains unknown. In contrast, the Knight home and studio at Rolleboise seems to have survived the war with minimal damage, although it is not clear how long the artist continued to paint there. (fig. 15)

The Paris address on his passport application—53 rue de Clichy—probably represents Knight’s final residence. Both Charles and Louis took up residence in Paris in the 1920s; Charles in the stylish 8th arrondissement and Louis in the more modern 16th arrondissement. Their addresses indicate that they were all financially secure, Charles with his architectural work and Louis Aston as a successful painter.

Daniel Ridgway Knight died of pneumonia at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine on March 9, 1924.[46] He was 85 years old. In a letter to Mrs. Nettie Dietz, a long-time family friend, Louis Aston Knight described his father’s passing: “He went to sleep holding my wife’s hand and never woke up.”[47] Funeral services were held on March 12, 1924, at the Church of the Holy Trinity, the American Cathedral of Paris, which had been such an important part of his life. He was buried next to his wife Rebecca in the cemetery at St. Germain-en-Laye just outside of Poissy.

Eight months later, on November 10, 1924, a retrospective exhibition was held at the John Levy Galleries in New York. The show included 75 works.[48] The following year, Louis and Charles consigned their father’s remaining artwork for sale at the American Art Galleries in New York, an art dealer that Daniel Ridgeway Knight had worked with for many years. The catalogue described the event as “comprising all of the remaining works belonging to the late Daniel Ridgway Knight.”[49] The sale was held on two separate days, February 4, 1925 featuring 95 of Knight’s paintings, and February 5, 1925, featuring 21 paintings.

Legacy

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Knight’s paintings continued to find a steady market, many of them being purchased by museums around the globe. Like other nineteenth-century Naturalist painters, his work became less popular in the wake of World War II when modernist art took center stage. Beginning in the late 1960s, there was a resurgence of interest in both Realist and Naturalist aesthetic values, prompting an art historical re-evaluation of nineteenth century developments that continues today. Daniel Ridgway Knight has a unique role in this process, in part because his position as an American painter working primarily in France is unusual. Like Mary Cassatt and James McNeill Whistler, his adult life was lived in Europe, and his return trips to the US were undertaken only in response to family circumstances and World War I. Unlike his fellow American expatriate colleagues, however, he chose to work within the French academic art world. Although he was initially fostered by Ernest Meissonier, Knight was an adept learner, mastering the idiosyncrasies of the Salon system and the organizational foibles of the Société des Artists Français. He thrived in both, and built a noteworthy career. One of the most poignant examples of this is that his donation of a painting for the charity exhibition sponsored by Société des Artistes Français and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1918 was accepted without question even though the rules specified that only French artists could submit artworks.

The situation of American artists in France—and Paris in particular—was unique. Most Americans sought formal training in Paris, but did not intend to remain there past their educational years. According to Lois Marie Fink, those who chose to live there on a more permanent basis were often seen as having “forfeited their cultural nationality and rendered themselves unable to paint a truly American picture.”[50] Critics in the US, in fact, often pointed to paintings of French peasants as un-American subjects, presumably because the US did not see itself as having a class system that would identify certain types of workers as peasants. “Even so, American collectors of contemporary art were attracted to them, while modest homeowners also enjoyed French rural scenes in the form of inexpensive chromo-reproductions.”[51] The National Academy of Design in New York was frequently anti-French, refusing what they deemed “Paris works” for exhibition as well denying membership to artists who were based in France. Needless to say, this attitude was ultimately counter-productive, prolonging the isolation of artists based exclusively in the US from the myriad new ideas circulating in Europe in the late nineteenth century.[52]

Daniel Ridgway Knight does not appear to have been especially concerned about defining himself exclusively as an American artist. Like many others, he found a community of artists in Paris that was composed of people from a variety of backgrounds. And he helped to nurture the American arts community, especially through his work at the Church of the Holy Trinity, the American Cathedral of Paris. By the 1890s, there were also a number of organizations devoted to American artists living in Paris, the American Art Association of Paris, the Paris Society of American Painters, and the Pen and Pencil Club to name just a few.[53] Living primarily in Poissy, however, Knight was closest to the artists involved in the Abbaye community, particularly Charles Meissonier and his family. His willingness to settle in France, to raise his children there and to participate in French life and culture set him apart, as did his disinterest in becoming affiliated with any of the American artists’ colonies in Brittany and Normandy. He was a genuinely cross-cultural figure at a time when that was rare for any American.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

[1] Archives, St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, 235 North 4th Street, Philadelphia, PA. “Baptisms,1839”, Record #216. Daniel’s older sister Rachel Aston Knight was also baptized here in 1836. See: Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S., Church and Town Records, 1669-2013 for Robert Knight. St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, 235 North 4th Street, Philadelphia, PA. Record #197.

[2] National Archives and Records Administration, United States Federal Census for Robt. T. Knight, Philadelphia, South Mulberry Ward, 1830, p. 27; and United States Federal Census for Robt. T. Knight, Philadelphia, South Mulberry Ward, 1840, p. 48. See also: National Archives and Records Administration, United States Federal Census, Guilford, Pennsylvania, 1850, p. 14. Guilford is just a few miles east of Chambersburg where Knight’s mother Anna Shyrock was born in 1804.

[3] National Archives and Records Administration, United States Federal Census, Philadelphia, Ward 14, District 41, 1860, p. 49.

[4] National Archives and Records Administration, United States Federal Census, Philadelphia, Ward 14, District 41, 1870, p. 35.

[5] The Philadelphia Academy of Art was established in 1805 by the painter, Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) in association with the neoclassical sculptor William Rush (1756-1833) and a number of local artists and businessmen. Their stated goal, published in the Academy’s Charter, was to “Promote the cultivation of the Fine Arts, in the United States of America, by […] exciting the efforts of artists, gradually to unfold, enlighten, and invigorate the talents of our Countrymen.” The curriculum at PAFA during these years was based on the model established by the Académie Française in the 1660s and later adopted by the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768. See the PAFA website at: https://www.pafa.org/about/history-pafa. For more information on the development of formal art academies in Europe, see Ingrid Vermeulen, Art and Its Geographies: Configuring Schools of Art in Europe (1550-1815). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024.This book is available through Open Access at Worldcat.org at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048553013.

[6] Susan Casteras, “The 1857-58 Exhibition of English Art in America and Critical Responses to Pre-Raphaelitism” in The New Path, Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites. Eds. Linda S. Ferber and William H. Gerdts. (New York: Schocken Books Inc., 1985) pp.109-133.

[7] National Archives and Records Administration, United States Federal Census, Philadelphia, Ward 14, District 41, 1860, p. 49.

[8] William Hauptmann’s excellent catalogue raisonné on Gleyre offers abundant information about the artist’s teaching atelier as well as the students who studied there. For more information, see: William Hauptman, Charles Gleyre (1806-1874): Life and Works / Catalogue Raisonné (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996).

[9] H. Barbara Weinberg, The Lure of Paris, Nineteenth Century American Painters and Their French Teachers (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1991) p. 63.

[10] Knight’s time in Italy is documented in the PAFA Annual Exhibition Record for 1865 and 1869, which lists his address in 1863 as “Rome”. See The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1807-1870, ed. Peter Hastings Falk (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1988).

[11] Elizabeth Johns, ed., One Hundred Stories: Highlights from the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, (Hagerstown, Maryland: Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in association with D. Giles Limited, London, 2008) p. 130.

[12] Archives, “Marriages, 1871”, Old St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, 1841-1898, 728 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

[13] Paul Tucker, “The First Impressionist Exhibition in Context”, The New Painting, Impressionism 1874-1886 (San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1986) 92-117. Tucker’s discussion of the historical context of Paris in the immediate aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War explains the key role of the arts in rebuilding France.

[14] There are a number of excellent studies of American collections and American collectors during the late nineteenth century. See: Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyer’s, Impressionism Comes to America, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1986.); Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., Collecting in the Gilded Age: Art Patronage in Pittsburgh, 1890-1910. (Hanover and London: Frick Art & Historical Center; University Press of New England, 1997); and Janet Whitmore, “Paintings, Collecting, and the Art Market in the Gilded Age: Minneapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, 1885-1920”. (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2002).

[15] Pope Boniface VIII canonized king Louis IX. See: Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Louis IX, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004). p 326.

[16] Agnès Guignard is not only a historian, but also a direct descendant of Ernest Meissonier who has studied the family’s correspondence in detail and written extensively on both her ancestors and the atelier of young painters who worked with them. In addition to Charles Meissonier and Knight, she identifies the following artists as Ernest Meissonier’s direct students: Edouard Detaille, Lucien Gros, Maurice Courant, Alphonse Moutte, and Georges Brétegnier. Joseph Gustave Peyronnet and Sidney Arbouin were there often, but not as consistently as the others. See: Agnès Guignard, “Meissonier et ses élèves”, Chronos, printemps, 2001, no. 43. pp. 15-22.

[17] Centre du Diffusion Artistique. Meissonier et ses élèves, Homage du bicentenaire. (Poissy : Ville de Poissy, 2015). p.33. Exhibition catalogue.

[18] Jérôme Delatour, Album Ridgway Knight, 1883, un maison de campagne à Poissy (Poissy, France : 1883).This is a photograph album that belonged to the architect, Charles Meissonier Knight, the second son of Daniel Ridgway Knight. The album contains photographs of the Knight family and their mansion in Poissy as well as twelve photographs of Knight’s paintings. It was purchased by the Bibliothèque National de France at auction on June 2, 2015 and is now in the collection of the Insitut nationale d’histoire de l’art, (INHA) in Paris. Delatour provides additional information about the Knight family properties in France based on documents from French official sources.

[19] Recensements de Population, Poissy,France, 1876. p. 29.

[20] Jean-Marc Denis. «L’enclos de l’Abbaye et ses ateliers» in Meissonier et ses élèves, Homage du bicentenaire. (Poissy : Ville de Poissy, 2015) pp.18-25. Exhibition catalogue.

[21] William H. Gerdts, “Impressions: American Painters in France, 1860-1930” in impressions: Americans in France, 1860-1930, and Claude Monet: Giverny and the North of France. (Naples, FL: Naples Museum of Art, 2007) pp. 9-21. Exhibition catalogue.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Kathleen Adler, Erica Hirschler and H. Barbara Weinberg, American in Paris, 1860-1900 (London: National Gallery Company, Ltd., 2006). Exhibition catalogue. Erica Hirschler’s essay “At Home in Paris” includes a discussion of the role of the American Cathedral as “an important social center” for American artists. 68.

[24] Cameron Allen, The History of the American Pro-Cathedral, Church of the Holy Trinity, Paris (1815-1980), (Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse LLC, 2012).

[25] The Legion d’Honneur does not keep dossiers on non-French members. Information about Daniel Ridgway Knight’s membership and activities was provided by Mme Minjollet of the Musée de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris on November 11, 2021.

[26] The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Philadelphia, Eighty-eighth Annual Report, February 5, 1894-February 4, 1895. (Philadelphia: 1895) p. 7.

[27] See the PAFA website: https://pafaarchives.org/s/digital/page/prizes

[28] “Col. Webster’s Active Career”, The Philadelphia Times, December 31, 1894. p. 16. See also “Col. Thomas Webster Buried”, The Philadelphia Times, January 2, 1895. p. 3. The burial notice reports that the service was performed by Reverend Doctor Paddock of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. Col. Thomas Webster is buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

[29] Catalogue illustré de Peinture et Sculpture, Salon de 1896, Ludovic Bascher, editeur. (Paris: Librairie d’art, Chamerot & Renouard, 1896.) p. 65.

[30] According to Jérôme Delatour, Knight purchased the property in Rolleboise in 1896.

[31] See Populations communales de 1876 à 2020 at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3698339

[32] “Daniel Ridgway Knight, Painter”, Brush and Pencil, Vol VII, No. 4 (January 1901): 193-207.

[33] Charles Meissonnier Knight married Alice Laure Elisabeth Boucherie on August 6, 1903, in Paris. By the time of Rebecca Knight’s death in 1909, they had two young children, ages four and three months.

[34] Marriage Records. New Jersey Marriages. New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, New Jersey.

[35] Rebecca Knight’s burial is recorded in the Parish Calendar of Holy Trinity Church, the American Cathedral of Paris. She was buried in St. Germain-en-Laye on August 9, 1909. See Cameron Allen, The History of the American Pro-Cathedral, Church of the Holy Trinity, Paris (1815-1980) (Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse LLC, 2012) 721.

[36] Archives de Paris, Acte de décès. 22 Octobre 1911. Raymond Knight, p. 132. See also: “Tué par la morphine”, L’Est républicain, 8819 (27 octobre 1911), p. 1, col. 4.

[37] Catalogue de tapisseries des SVII3 et WVIIIe siècles—importante suite de six tapisseries de Bruges de la série des Sciences et des Arts, d’après les cartons de l’atelier de Rubens ayant fait partie de la collection de M. Ridgway Knight, artiste peintre, (Paris: Hotel Drouot, jeudi, 10 mars 1910). See also Gallica: http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41536677s

[38] Nancy L. Green, “Americans Abroad and the Uses of Citizenship: Paris, 1914-1940”, Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Spring 2012) 5-32.

[39] Louis’s application was filed on January 15, 1915; his address was 147 rue de la Pompe. Daniel applied March 1915, listing his address at 53 rue de Clichy. Charles’ application was submitted on July 29, 1915, with an address at 11 rue Marbeuf. Because both Louis and Charles were born in France, they based their claim to US citizenship on their father’s birth in Philadelphia. See National Archives and Records Administration, US Department of State, Department Passport Application. Form 176-Consular.

[40] For a fuller discussion of this issue, see: Nancy L. Green, “Americans Abroad and the Uses of Citizenship: Paris, 1914-1940”, Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Spring 2012) 5-32.

[41] Exposition au profit des oeuvres de guerre de la Société des Artists Français et de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. (Paris, 1918) p. 22. Knight’s entry is No. 265. See: gallica.bnf/ark:/12148/bpt6k65651125.textimage

[42] My sincere thanks go to Kate Thweat, archivist at the American Cathedral of Paris for her time and diligence in tracking down information about the Knight family’s membership at the church.

[43] See Jérôme Delatour, Album Ridgway Knight, 1883. np.

[44] This information was graciously provided by Charles Knight’s granddaughter in an interview in 2021.

[45] According to Jérôme Delatour, “It is also unknown whether Ridgway Knight had any connection with Casimir Crosnier Leconte before the sale of his house, but Marie-Laure Crosnier-Leconte, granddaughter of the latter, is still in possession of a sketchbook made by the painter around 1892.” [On ignore également si Ridgway Knight avait quelque lien avec Casimir Crosnier Leconte avant la vente de sa maison, mais Marie-Laure Crosnier-Leconte, petite-fille de ce dernier, est encore en possession d’un carnet de croquis réalisés par le peintre autour de 1892.]

[46] American Consular Service, Report of the Death of an American Citizen, Daniel Ridgway Knight. March 15, 1924, Paris, France. File 330 K. Died of Pneumonia at 3:00pm on March 9, 1924. report filed by Aston L. Knight (147 rue de la Pompe) and Charles Knight (11 rue Marbeuf) in Paris. Signed by A. M. Thackara, Consul-General of the United States of America. Form No. 192-Consular.

[47] Letter from Louis Aston Knight to Nettie Dietz. 1924. Letter courtesy of Sara Knight, who provided invaluable assistance with family information. Charles and Nettie Dietz of Omaha, Nebraska, were frequent clients of Daniel Ridgway Knight. Dietz was a lumber baron in Omaha and the owner of several coal mines. After his retirement in 1908, he and his wife traveled extensively, in part collecting a variet y of objects from all parts of the world. They visited Daniel Ridgway Knight in Paris in the years before World War I, and undoubtedly were acquainted with Louis Aston Knight as well.

[48] For more information on John Levy Galleries, see the Archives of American Art at: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/john-levy-galleries-scrapbook-6437. See also the Frick Collection Archives Direction for the History of Collecting at: https://research.frick.org/directory/detail/465

[49] American Art Galleries, Catalogue comprising all of the remaining works belonging to the late Daniel Ridgway Knight. (New York: 1925).

[50] Lois Marie Fink, “Reactions to a French Role in Nineteenth-Century American Art” in American Artists, The Louvre. eds. Elizabeth Kennedy and Oliver Meslay (Vanves, France: Hazah (Hachette Ilustré),2006). p. 25. Terra Foundation for American Art and Louvre. Exhibition catalogue.

[51] Ibid.

[52] It should be noted that new ideas did creep into the US culture through two somewhat unexpected art forms. The first was Japonisme, which appeared in the US at least by 1880, and the second was architecture, which saw startling new developments in the creation of a uniquely American design in Chicago after the Great Fire of 1871. Neither architecture nor decorative arts are typically leaders in aesthetic change, but in this case, external business pressures facilitated the process as a strategy for improving commercial progress.

[53] See Emily Burns, “Of a Kind Hitherto Unknown”” The American Art Association of Paris in 1908”, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Vol. 14, Issue 1, Spring 2015. [https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring15/burns-on-the-american-art-association-of-paris-in-1908] Additional research is needed to determine the scope and purpose of all of these organizations as well as their membership lists.